The blue light from your phone isn't what's keeping you up at night.

The truth is simpler than that. Let's dig into some of the research and how so many of us got this one thing so wrong.

Huberman’s back at it again!

This time selling red lense glasses to filter out the blue and green wavelengths. Let me save you 200USD.

I won’t bother talking about why blue light blocking glasses are a waste of your money, thankfully Health Nerd has already covered that. If you’re interested in a banging study on it, click here, or just read the highlights below.

Spectrophotometric properties of commercially available blue blockers across multiple lighting conditions (2021).

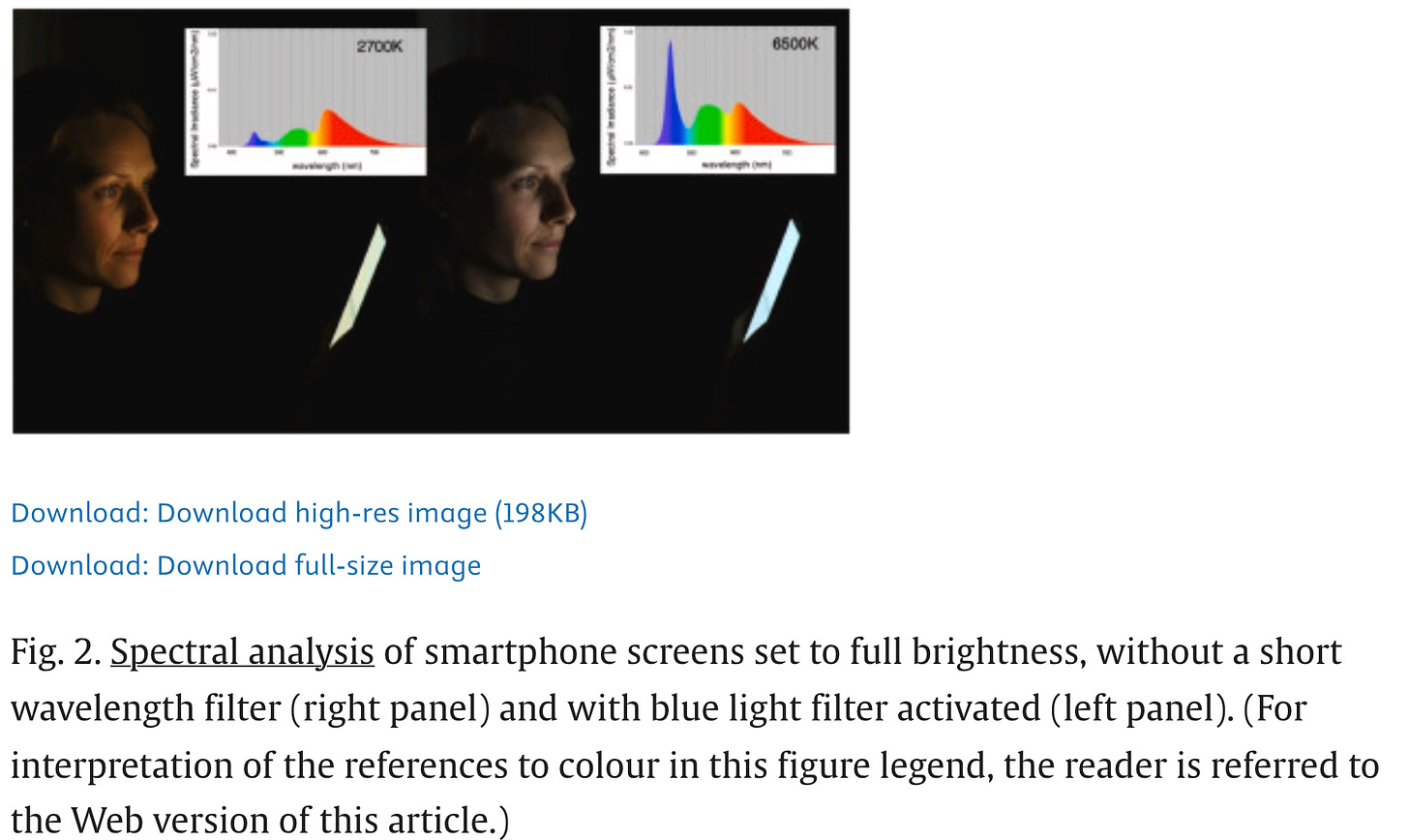

This study took a closer look at 50 different types of lenses to see how well they block blue light under different lighting: blue LEDs, tablet screens, regular indoor lights, and sunlight.

To measure their effectiveness, researchers checked how much light each lens blocked across the spectrum and looked specifically at the wavelengths that affect our circadian rhythms the most (455–560 nm). They divided the lenses by tint and compared them:

red-tinted lenses blocked the most sleep-disrupting light

blue-tinted lenses blocked the least (yes, ironic!)

Orange lenses were in the middle… they blocked similar amounts of circadian-light as the red lenses but allowed through a bit more light overall, so they may give a clearer view while still blocking those wavelengths.

Ok so does this mean Huberman is on to something? Not really. I want to talk about the fact that all of this ‘blue light’ nonsense is a moot point in the first place, and how the studies have been misunderstood or misinterpreted.

→ Yes, blue light from screens can reduce melatonin levels, but not nearly to the extent some claims would have us believe.

→ It doesn’t completely “wipe out” melatonin, and defo doesn’t halt melatonin production altogether.

→ It can cause a decrease in melatonin of around 50%… HOWEVER, this drop in melatonin doesn’t necessarily mean people will struggle to fall asleep.

Let me point you in the direction of a world class meta analysis by Gradisar and his team in Aussie. Let’s talk about point 1.1. You can open the paper and follow along, or just accept my chat gpt summary of the points:

After early studies in the 2010s, scientists began seriously investigating the impact of bright screens on melatonin and alertness before bed. In one study, Cajochen and his team spent five hours comparing the effects of a bright laptop screen with a dim one in the evening, using a mostly white background. They found that bright screens reduced melatonin levels and increased alertness before sleep, but they didn’t measure the effects on actual sleep.

Then in 2012, Wood et al. did a similar study, looking at one-hour versus two-hour sessions with bright or dim tablet screens. Their findings were consistent with Cajochen's team: bright screens suppressed melatonin, but only after two hours, not one. Again, sleep itself wasn’t measured.

You see where this is going?

I did a semester of law and have watched countless courtroom series. In the legal system this would be circumstantial evidence.

In science, it’s known as biological plausibility bias or the fallacy of causal inference. This happens when people see a plausible biological connection and infer causation without sufficient evidence that the biological factor is actually having an effect. This kind of inference can lead to correlation-causation bias, where observed correlations are mistaken for evidence of causation due to biological reasoning alone. This can result in people overestimating the impact of certain biological factors (like blue light on sleep) without thorough testing of alternative explanations.

So Michael Gradisar and his team did their own research.

They compared three screen settings one hour before bed:

bright

dim

and bright with a blue-light reduction app (f.lux)

It’s worth noting they didn’t measure melatonin, but they did see increased alertness from the bright screen (supporting Cajochen’s findings).

HOWEVER, the bright screen only delayed sleep onset by about three minutes compared to the dim setting.

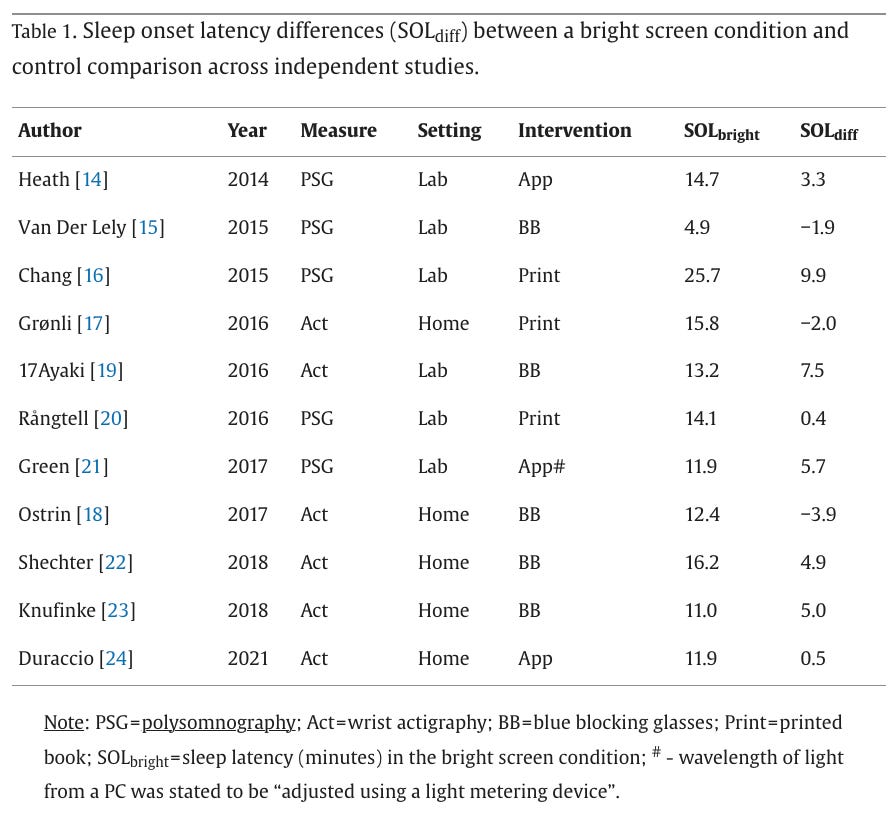

Moreover, the following year, van der Lely’s team added a twist, studying bright screens with and without blue-light-blocking glasses three hours before bed. They found that melatonin suppression started after about 1.5 hours of bright screen use, a bit sooner than in Wood's study. However, their findings also confirmed that the effect on sleep onset was minimal, with only a slight difference of around two minutes for those without blue-light glasses.

‘Okay but this is just in one night, right?’

Correct.

Most people use screens every night, so this was addressed in another study by Chang where they compared five consecutive nights of reading an e-book on a screen versus a printed book under dim light.

The result?

They found only a slight difference of about 10 minutes in sleep onset between the two, though they did see a 90-minute delay in the timing of melatonin release.

Since then, more studies (Table 1) have examined bright screens’ impact on sleep.

What this all means:

→ Although bright screens consistently suppress melatonin, their effect on sleep latency remains small, sometimes even shorter than in the dim or printed book conditions. This consistency across various studies (including in teens, athletes, insomniacs, and everyday sleepers) suggests that we may continue to see similar results moving forward.

While bright screens cause small extensions in sleep latency, melatonin suppression remains a constant effect.

These findings hint that perhaps …. melatonin levels and the time it takes to fall asleep may not be as tightly connected as previously thought.

This paper was published in August 2024, and resulted in Matt Walker (world renowned Sleep Scientist) to correct his stance which he wrote about in the bestselling book Why we Sleep.

So there, Matt Walker apologised, can you trust me now?

That begs the question:

What’s really keeping you up at night?

Lots of love,

Anne-Sophie

V. Interesting. I did wear blue light glasses for a couple of years due to the "revolutionary understanding" that it significantly effects sleep - clearly that was time and money wasted. Nice to see someone presenting detail in a digestible manner, backed by science - which is what most people thought Huberman was doing.. NOT ME ANYMORE. Thank you - keep up the insightful and joyous reads :D